‘What you don’t measure, you can’t manage’ has long been a common turn of phrase in the agriculture industry, but soon it could be more than that.

‘What you don’t measure, you can’t manage’ has long been a common turn of phrase in the agriculture industry, but soon it could be more than that.

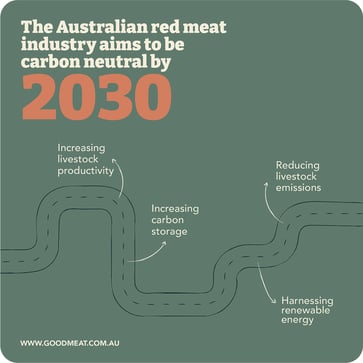

As the clock ticks down on the red meat industry’s pledge to be carbon neutral by 2030, the collection of data will be paramount for every operation, and carbon accounting is going to be a normal part of business.

So says grazier Fiona Conroy, who farms with her husband, Cam Nicholson, on the Bellarine Peninsula in southern Victoria.

For them, the collection of data began more than 30 years ago.

“Our goal is to be productive, to do the right thing and try to be good farmers,” Ms Conroy said.

“We want to look after our environment, our animals and the people in the business, and we want to generate a profit so we can keep putting money back into the business.

“We’ve always tried to adopt best practice and the classic thing about best practice is that it keeps changing, so you’ve got to keep changing what you do.”

Operating across almost 400 hectares, the couple “measure a lot of data”.

“We run a self-replacing commercial Angus herd that is BreedPlan recorded, where we join 220 to 250 cows a year, depending on the season,” Ms Conroy said.

“It is a progeny test herd for Te Mania, and we produce feeder steers for the long-fed market, selling to Stockyard and Rangers Valley.”

They also run a self-replacing superfine Merino flock, joining about 700 Merino ewes, and a flock of wethers.

All those animals make for a large amount of data.

“We measure stocking rate and animal production, so we regularly weigh stock and use NLIS tags to record data against individual animals using KoolCollect,” Ms Conroy said.

“As part of BreedPlan, we record each calf’s sire and dam, birth weight, calving ease, gestation length, 200-day weight, 400-day weight, and at 400-day weight all our young cattle are scanned for P8 fat, rib fat, intramuscular fat and eye muscle area.

“When the steer portion go off and are fed and then slaughtered, the carcase data goes back into BreedPlan .”

When it comes to their sheep, an investment in a Te Pari sheep handler 18 months ago has made recording data against individual sheep NLIS tags easier.

“We’re recording preg scanning results (singles, twins or empties ), ewe conditions score at key times of the year, whether ewes are wet or dry at weaning, and if lambs are born from a single or multiple pregnancy,” Ms Conroy said.

“We also measure lambing paddock performance, which includes ewe mortalities and number of lambs born in each paddock to rank paddocks on lamb survival.

“Three years ago, we started to mid-side sample and weigh the fleeces of our ewe hoggets at shearing and record off-shears body weights, which are used to select replacement ewes.”

They also record stock movements in and out of paddocks using Mobble, so they know the number of stock that have been in paddocks and for how long.

But it’s not just animal production data being measured, there’s also a lot of soil and pasture production data.

"We’ve soil tested a third of the farm every year for the past 30 years,” Ms Conroy said.

“That involves taking 20-30 samples to a depth of 10 centimetres across each paddock using a grid pattern with GPS, looking at things like potassium, phosphorus, sulphur, and cation exchange capacity, but has also included carbon.

“Late last year, we did one metre soil cores in line with the Australian Carbon Credit Units protocol.”

Production gains

Using this data to make management decisions has culminated in Ms Conroy and Mr Nicholson being able to double the stocking rate on their property over the past 30 years.

“We’ve undergone a farm development program over that timeframe, which involved land-class fencing according to soil type and then matching different pasture types to different soil types,” Ms Conroy said.

“We’ve reduced the number of paddocks, we’ve increased the fertility because of all the soil testing and working out what needs to be applied to get the right soil conditions, and then we’ve gone in and established perennial pastures."

They’ve also undertaken extensive tree plantations since the 1980s and ‘90s.

“There’re probably 35 different tree plantations and about 10 per cent of the farm is now under trees.

“Part of that farm development initially involved double fencing boundary fences with adjoining properties and then planting trees.

“Then when we did the paddock subdivision, we gradually double fenced them, so all the paddocks tend to have trees between them.

“We’ve got a whole range of different tree plantations, but we’ve kept records of when they were planted and what’s in them.”

The path to carbon neutrality

Becoming carbon neutral has never solely been the goal for Ms Conroy and Mr Nicholson.

“We planted trees for biosecurity, to stop erosion, for biodiversity, and animal welfare like shade and shelter,” Ms Conroy said.

“That’s always been the way we’ve approached farming and it’s the same with improving soils; you want to optimise soil health, optimise pasture growth, and optimise production.

“That all goes hand in hand with increasing carbon levels in your soil, but it’s not like we’ve been driven by carbon; it just happens to be part of what we do.”

There came a point, though, when the couple began to wonder if their operation was carbon neutral.

“We’ve been able to model how much carbon has been sequestered in those trees - and this is conservatively modelled - using a computer model called FullCAM,” Ms Conroy said.

“Because we’ve got this bank of soil data, we’ve also been able to look at how soil carbon has changed as we’ve gone about improving soil fertility and putting perennial pastures in, and we can see that it jumps up and down depending on, it would appear, annual rainfall.

“We’ve been able to model where our soil carbon is going in the top 10cm and then we’ve been able to extrapolate that using the CSIRO’s SCaRP model, which says, as a rule, 50pc of your soil carbon in the top 30cm is actually sitting in the top 10cm.

“So, we’ve been modelling sequestration with trees and sequestration in the top 30cm of our soils to look at where our carbon sequestration is going.”

On the other side of the equation is measuring their emissions.

“We’ve always kept a spreadsheet of stock numbers and stock class types for each month, and we can work out their emissions each month, then model what our emissions are doing for the year,” Ms Conroy said.

Using the Farm Greenhouse Accounting Framework tools, which enable farmers to model emissions for a variety of production systems, Ms Conroy and Mr Nicholson have identified that 97pc of their operation’s emissions come from livestock. Of those emissions, 88pc are in the form of methane.

The methane challenge

“One of the challenges is greenhouse gas emissions are all discussed in terms of carbon dioxide, but there’s a whole heap of different emissions like nitrous oxide and methane, and they have to be converted to what their equivalent in CO2 emissions is,” Ms Conroy said.

“The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) determines what weighting gases like nitrous oxide and methane have in terms of their CO2 equivalence and these are regularly updated as an assessment review.

“When the global warming potential (GWP) of methane changes, it has a massive impact on your ability to sequester and offset methane and be carbon neutral.”

From 2008/09 to 2014/15, the global warming potential of one methane molecule was equivalent to 21 CO2 molecules. In 2020/21, that weighting increased to 28.

“When the global warming potential of methane was 21, with the trees and the soil, we’d been carbon neutral since about 2007,” Ms Conroy said.

“When the global warming potential of methane moved from 21 to 28 - which is a 30pc increase - suddenly our total emissions increased overnight.

“We went back retrospectively and looked at how the new GWP factor for methane impacted on our emissions, and found we have now only been carbon neutral since 2017 and we will probably not be carbon neutral at the end of this financial year.”

Shifting goalposts and the carbon credits debate

It’s these shifting goalposts which have Ms Conroy questioning the sustainability of being carbon neutral.

“I want to give credit to MLA for making the CN30 commitment, because it meant they’ve put a lot of effort into research and development,” she said.

“Often, reducing emissions really involves just being more efficient, and that makes money for your business as well.”

But it’s the sale of carbon credits that concerns her most.

Ms Conroy made headlines recently when she told the ABARES Outlook 2023 conference “I’d rather die than sell carbon credits”.

It’s a position seemingly at odds with the current rhetoric, which points to carbon credits as being an alternative income stream for farmers.

“All this talk about ‘easy money’ by sequestering soil carbon and selling carbon credits is often not based on solid science,” she said.

“It ignores the reality that soil testing for carbon is highly variable and soil carbon levels can drop in dry seasons, which is highly likely given the increased chance of drier seasons more often with climate change.

“And if you sell your soil carbon, you are then responsible for managing your land for the person who has bought that carbon, because you have made a commitment that it will be there in possibly 25 years’ time.”

Ms Conroy said selling soil carbon involves the farmer carrying all the risk, and potentially losing a lot of flexibility in their farm management.

“Selling carbon also removes from the equation a livestock producer’s ability to use that carbon to offset their own emissions from livestock, which could limit their marketing opportunities in the future.”

The way forward for farmers

At the end of the day, being successful in this space all comes back to data collection.

“Understand what your emissions are, understand what your potential for sequestration is, understand what your emissions intensity is, look at where markets are going, but don’t rush off and sell your carbon just yet,” Ms Conroy said.

“It’s your soil, it’s your farm, it’s your business - be conservative.”

Results

Results-3.png)