There’s something incredibly special about properties that have been passed down the generations. It’s a mix of pride, passion and love that underpins a dogged determination to keep the family legacy alive, preserve the memories and create many more for the generations to come. Bungaree Station is one such property.

There’s something incredibly special about properties that have been passed down the generations. It’s a mix of pride, passion and love that underpins a dogged determination to keep the family legacy alive, preserve the memories and create many more for the generations to come. Bungaree Station is one such property.

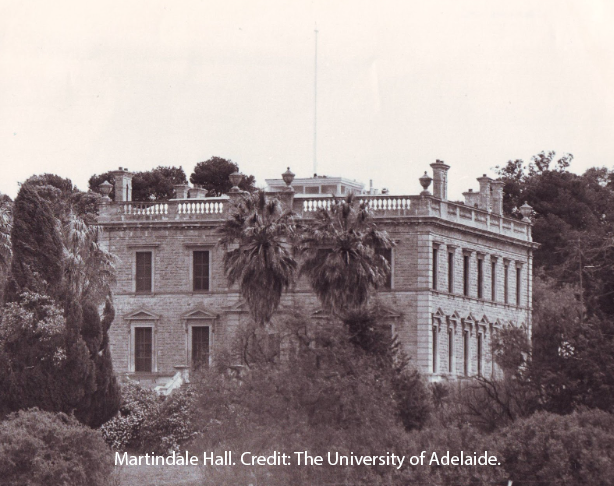

Nestled in the rich, picturesque Clare Valley in South Australia, about 140 kilometres north of Adelaide, Bungaree Station’s landmarks and treasures reveal a window into a prosperous wool-growing past. The buildings have been so well preserved that the main homestead is still enjoyed by the fourth, fifth and sixth generations of the Hawker family.

The story of Bungaree Station goes back more than 180 years. As any farming family knows, there’s no days off and Christmas Day is no exception. It was on Christmas Day 1841 that George Charles Hawker and his brothers, James and Charles from Hampshire, England, decided upon the site for their ‘head station’.

George, 23, recognised the rich land with its plentiful supply of eight foot deep drinking water as the perfect site for the 2000 ewes the brothers had bought in Carcoar, NSW. They pulled up stumps and coined the property after the Aboriginal name for the area. Aptly, it means ‘place of deep water’.

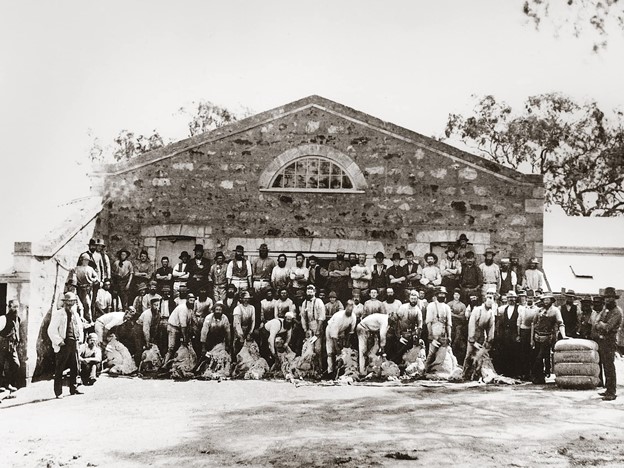

Shearing team at Bungaree,1882. Credit: bungareestation.com

Shearing team at Bungaree,1882. Credit: bungareestation.com

At a time when Australia was said to ‘ride on the sheep’s back’, by the 1880s Bungaree was running 100,000 merino sheep on almost 70,000 hectares. It was now home to one of Australia’s most thriving flocks and became a bustling village in its own right. More than 50 staff and their families called Bungaree home and a church, blacksmith shop, school, store, council chambers and the woolshed were built from sandstone quarried nearby. Staff cottages, the manager’s house, homestead and shearers quarters all housed the many employees. A visitor to Bungaree in 1878 documented his surprise to see 54 shearers and over 80 hands employed, with work going on with the ‘regularity of clockwork.’

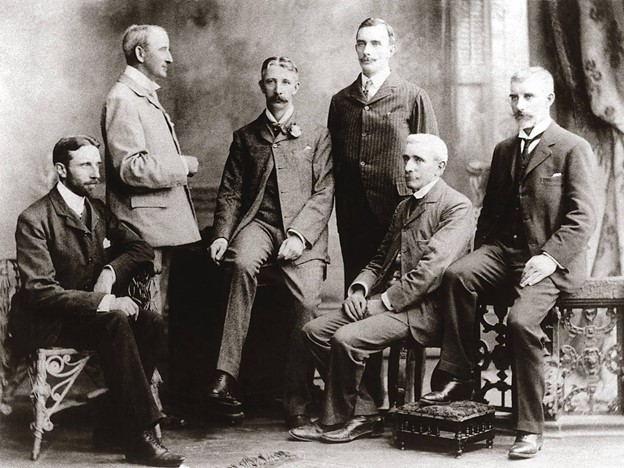

GC Hawker's sons, 1906

GC Hawker's sons, 1906

George had 16 children and after his death in 1895 six of his sons ran Bungaree. In 1906 they divided it among the six brothers. After one of the sons died, seventh son Richard McDonnell Hawker took on the homestead block. Today his grandson George runs the property with wife Sally.

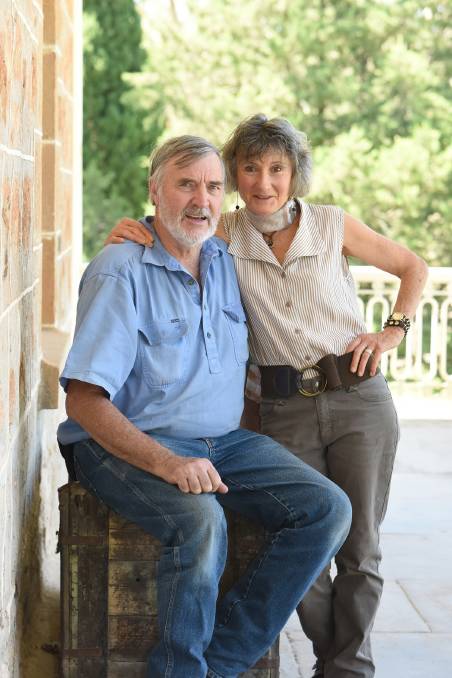

Sally left her homeland South Africa in the 1970s, determined to find the best farming practices to later take over her father’s farm. But after meeting her husband-to-be in hospital while he recovered from fire injuries, a welcoming handshake and some friendly chit chat changed her path. The couple married in 1974 and had three children.

George and Sally Hawker at Bungaree Station, pictured in 2017 Photo KAREN JERICHO

George and Sally Hawker at Bungaree Station, pictured in 2017 Photo KAREN JERICHO

Their son Edward manages the day-to-day farming role. Cereal cropping supports the sheep flock, still a vital part of the business. The heritage-listed station is also a unique destination for conferences, weddings and tours. The couple’s daughter Vicky and her husband Mark hold the reins to the thriving tourism and hospitality business. Its beautifully renovated 1850s cottages attract many looking for a country escape. You can even enjoy some Bungaree lamb from the Station Store while immersing yourself in the property’s pastoral heritage. Although you won’t find a dozen girths or bottles of strychnine, as documented in the Bungaree List of Stores and Rations, 31 December 1897, many of the historical products from those early days are still displayed on the shelves.

Summer Harvest

The Clare Valley has thrived in recent times as we rediscover our own backyard. In 2021 the region reached $134 million in tourism expenditure - its 2025 target. Bungaree Station has flourished, but like all farming enterprises, it’s had its fair share of tough times.

The recession of 1991-92 saw Bungaree spiral. The Hawkers could not sell their sheep. In a 1993 interview with the Salt Lake Tribune, Sally tearfully described the devastation the family suffered when they were forced to cull 1000 head of sheep. Even giving them away to charity had proved impossible. With a $3 a head tax, plus $15 each to have them butchered, it left the Hawkers facing an insurmountable expense of at least $15,000.

.jpg?width=953&name=The%20woolshed%20at%20Bungaree%20Station%20in%20the%201920s%2c%20that%20sits%20in%20the%20SA%20Government%20Photographic%20Collection%20(GN07458).jpg)

The woolshed at Bungaree Station in the 1920s, that sits in the SA Government Photographic Collection

Determined to honour the legacy built by George’s great, great grandfather and ensure Bungaree stood proudly in the family’s name in the future, Sally turned to sheep in an unlikely form. She began making chocolate sheep to sell for additional income at the Station Store and sold them for $2 a piece.

“The chocolate sheep saved us,” Sally told The Salt Lake Tribune.

Through the ups and downs, the celebrations and the tragedies, the Hawker family’s passion and unwavering resolution to cherish and share the history of Bungaree Station has held strong. It’s a lasting reminder of South Australia’s pioneering past and the people who created the historic station we enjoy today.

.jpg?width=1105&name=EXTENSIVE%20FLOCK%20A%20sheep%20sale%20at%20Bungaree%20Station%20in%201925%20stockjournal.com.au%20(2).jpg)

A sheep sale at Bungaree Station in 1925 stockjournal.com.au

Results

Results