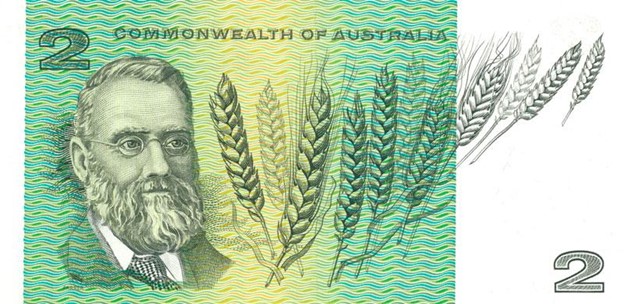

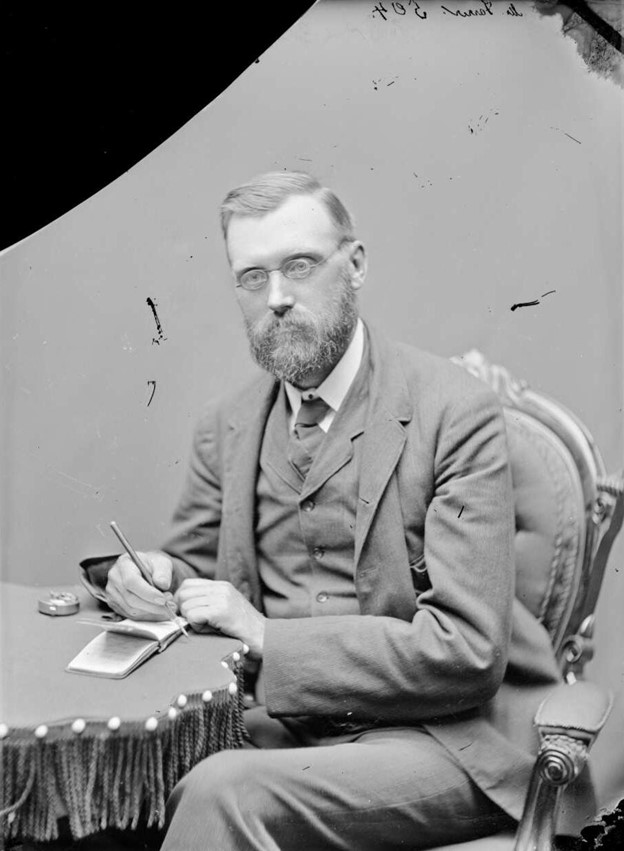

William Farrer didn't live to see his face emblazoned on the $2 note but his legacy, quite literally, has roots in farming today. Revered as ‘the father of wheat’, Farrer developed the first strain of drought resistant wheat at the heritage-listed Lambrigg Homestead near Tharwa, ACT.

The 25-year-old Englishman migrated to Australia in 1870 in the hopes the warmer climate might improve his tuberculosis. Hailing from a farming family, he was bent on buying a sheep station but when the funds fell short he became a surveyor and worked for the NSW Department of Lands for more than a decade.

Upon marrying Nina De Salis in 1882, Nina’s father forewent the dinner set and gifted the couple 240 acres near his own property instead. William crowned the land ‘Lambrigg Station’, meaning “hill of lambs”, in a nostalgic reference to his family’s home in north-west England.

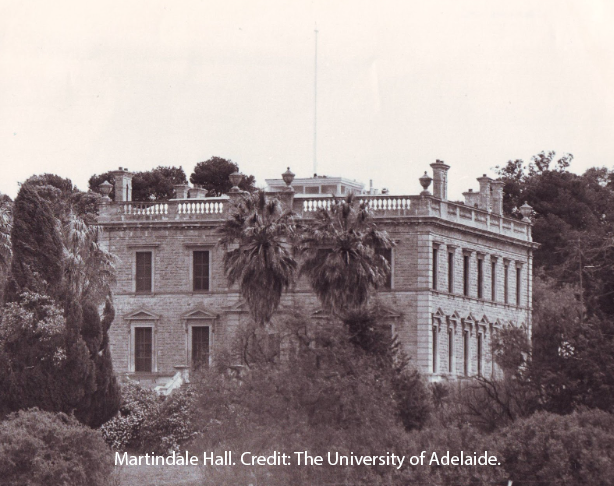

In 1894 the homestead was completed. The bottom floor was built on stone foundations with pise walls. On top was a timber base of Oregon imported from North America. Handmade bricks adorn the top storey. William’s surveying experience meant the house was built in a protected site and basks in the northerly winter sun. Wide verandahs on three sides provide a sanctuary in summer.

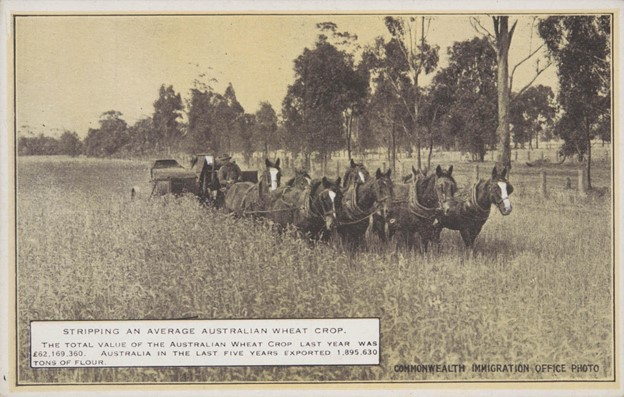

But it was in a little cottage on the right as you drive towards Lambrigg where the science that changed the Australian agriculture scene in the 1900s evolved. Farrer’s laboratory was built a few years before and overlooked the paddock he used for his experiments. After planting the many wheat seeds he’d collected from around the world to see which one flourished, he began cross-breeding the strongest varieties. Revolutionary at the time, Farrer was one of the first in the world to experiment with plant hybridisation. He was passionate about developing a wheat variety that was resistant to black rust, grew well in Australia’s hot and dry climate and made quality flour.

Farrer’s precious field notebook offers a remarkable glimpse into his purpose. Hundreds of experiments are recorded, every one of them requiring meticulous care to pollinate wheat flowers by hand. His resolve was unwavering - Farrer even turned down the family fortune in England in favour of continuing his work at Lambrigg Station. At last, his breakthrough came in 1897. Yandilla wheat was cross-bred with Purple Straw wheat and the new variety proved productive and disease resistant. A triumphant Farrer named it Federation’ in honour of the creation of the Australian nation in 1901. Federation wheat was distributed in 1903 and wheat farmers quickly began to grow the new variety. From 1910 to 1925 Federation was the most popular variety of wheat in Australia.

Sadly, like Vincent van Gogh and Emily Dickinson, Farrer knew little of his success. He died in 1906 after suffering a heart attack. At dusk the following day he was laid to rest on a hill at Lambrigg overlooking his beloved crops. The Australian $2 note immortalized Farrer and Federation wheat from 1966-1988.

Today, Lambrigg Station is owned by Kate and Peter Gullet and has been in the family since the 1940s. The couple run sheep and cattle on the 730-hectare property, one that still sports the profound effects of Farrer’s foresight. "Farrer blessed us with his willingness to plant things that don't give an immediate effect," Peter shared in an interview with Country Style magazine.

"He committed to the longer term."

That investment shines through in the breathtaking gardens that feature some of the trees Farrer planted, including Lebanese cedars, an English oak, three Himalayan cedars, an Irish strawberry tree and an enormous pencil pine.

Peter’s parents Ruth and Jo continued the tradition of planting trees when they owned Lambrigg. More than 60 years on an array of beautiful, mature trees stand proudly among Farrer’s plantings. As a young boy growing up on Lambrigg, Peter planted an acorn in the north western corner of the garden and today a stunning English Oak is a testament to the long view.

So too is the humble cottage that still remains on Lambrigg today. From within its rammed earth walls and flagstone floors came the dogged determination that revolutionized Australia’s wheat industry.

Results

Results